- About Sharon Watts

- Miss You, Pat: Collected Memories of NY’s Bravest of the Brave, Captain Patrick J. Brown

- Mildred Pierce: A Peekskill Production – Hudson Valley Magazine

- Zen I Can (an hour at a time)

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Herbalist Brad Teasdale

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Body & Spirit / Tibetan Medical Paintings

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Herbalist Julia Graves

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Serving Those Who Serve.org

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Beryl Bender Birch

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Dr. Richard Brown on the Healing Power of the Breath

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Photographer Maxine Henryson

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on art exhibit at The Kitchen

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Cyndi Lee

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Artist Elizabeth Riggle

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on The Rubin Museum of Art

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Yoga Therapy

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Photographer Lisa Ross

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Smithsonian Curator of “Yoga: The Art of Transformation”

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Robert Sturman, Photographer

- YogaCity NYC ~ interview with Artist Chris Soria

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Curandera Josie Casteneda

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Artist Robin Gaynes-Bachman

- YogaCity NYC ~ article on Prayer Bead Exhibit at the Rubin Museum

- YogaCity NYC ~ interview with Artist Chrysanne Stathacos

- YogaCity NYC ~ article on “Bodies In Balance”exhibit at the Rubin Museum of Art

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Yogi/Artist Robin Ann Meyer

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on “Lost Kingdoms” exhibit at The Met

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Judith Hanson Lasater

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Artist Gigi Spratley

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Anthropologist Carroll Dunham

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Sacred Arts Research Foundation

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Nicholas Roerich

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Tania Kazi on Rumi Immersion Workshop

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Sokhna Heathyre, Spiritual Health Feminist

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Green Tea

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Coconut Oil Cleanse

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Anneke Lucas of Liberation Prison Yoga

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Whitney Chapman on Yoga for Parkinson’s Disease

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Amy Matthews’ Babies! yoga class

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Gods In Print

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Chinese Cupping Treatment

- YogaCity NYC ~ article on Sacred Spaces at the Rubin Museum of Art

- YogaCity NYC ~ interview with a Yoga-Psychotherapist

- YogaCity NYC ~ article on Creating a Personal Shrine

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on “Encountering Vishnu” exhibit at the Met

- YogaCityNYC ~ article on Integral Yoga “Sleepover with a Guru”

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Vedic Astrologer Kari Field

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Botanist Lisa King

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Sculptor Noah Baumwoll

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Bryant Mascarenhas / Yoga for Mental Health and Addiction

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with hOM’s Ryan Freed

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Richard Villella

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Feminist Buddhist Amber Bemak

- Yoga City NYC ~ article on Female Empowerment Tour

- Yoga City NYC ~ interview with Bill Auerbach on Queer Dharma

- YogaCityNYC ~ article OM LAB

- YogaCityNYC ~ interview with Eve Holbrook

Bert Sommer — Shindig! Issue #94

There he was again—the tall, gangly kid with the tangled mop of hair, his floppy sneaker laces dragging around the stage as The Vagrants set up. What was he, 16? 17? He’d lean in and exchange notes with the band’s leader (Leslie—four years older and nearly triple the girth), whose wicked guitar licks were zapping the north shore of Long Island out of its Mid-60s suburban stupor. The kid always left the stage after the soundcheck.

Ira Stone made this observation at The Action House, a large music club in Island Park, New York. He knew the big guy from jamming regularly in the basements and garages of split-level homes, and at local club gigs. Under Leslie, his mentor, Ira learned to play a mean Stratocaster, himself. What Ira did not yet know was that in three years he would answer an ad for a guitar player, placed in The Village Voice by this very same skinny guy with the mile-wide Afro—and within weeks they would be helicoptered into the middle of a cow pasture in upstate New York, and become a part of history.

Glenn Friedman was one of the lucky early arrivals able to secure a spot of prime real estate 200 feet from the Woodstock stage. The burnt incense of sawdust still lingered in the warm August air. It was Friday, and the crowd of 300,000 (and growing) was expectant, yet mellow. Armed with a two-day pass, he eagerly anticipated Jefferson Airplane and The Who. Two acts had already performed that afternoon—Richie Havens opened just to get the late-running event started, but, contrary to myth, did not perform for hours on end. Psychedelic folk group Sweetwater followed, coincidentally introducing their set with ‘Motherless Child,’ the same song Havens had ended with, entwined with the improvised ‘Freedom.’

Sri Swami Satchidananda blessed the event as a slow sunset’s glow began to backlight the next performer, accompanied by a polite announcement. “Let’s welcome Mr. Bert Sommers [sic] and some of his friends.”

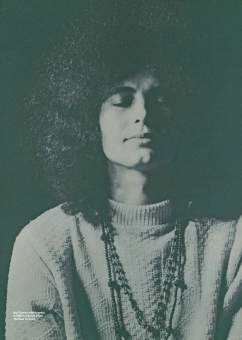

The barefoot, unknown singer with cherub lips and fuzzy halo folded his long legs into a casual lotus seat, then took a moment to tune his guitar. He calmly centered himself, as if this was where he was meant to be at the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.

“I know that guy!” Glenn nudged his friends excitedly. Not only had he recently bought Bert’s debut album The Road to Travel at E.J. Korvette, they also had been classmates.

Like many others across the country, the 1967 “Summer of Love” graduating class at Woodlands High School had been trapped in an aspic of leftover Eisenhower-era ethics. Heavy drug use wasn’t mainstream, but sneaking shots of J&B between swishes of Lavoris mouthwash was. The polarizing issue easiest to focus on (as Vietnam loomed above all) was hair. Long hair. On boys! Like Bert.

“Everyone knew everyone,” Glenn recalls. Yet Bert Sommer was a bit of a ghost, showing up for class only on occasion. But when he did, “Girls went ga-ga. He was quiet. There was something different about him.”

Bert was a self-taught artist discovering his gifts: writing poetry that blossomed into complex lyrics, plucking simple—then more sophisticated—chords on his guitar, and exploring a voice that verged on the astral. Meanwhile, he found a niche with musician mates so much more comfortable than his own divided family scene.

Glenn witnessed his enigmatic classmate open the 10-song set with ‘Jennifer’ and end with ‘Smile.’ He joined in Woodstock’s first standing ovation for Bert’s cover of Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘America.’ And he marvels, 50 years later: “The whole thing just blew my mind.”

The internal combustion of teen angst and hormones doesn’t stake more of a claim on any one generation, but many in 1967 felt otherwise. The arrival of The Beatles just after the assassination of JFK nuked open a new frontier. And for boys, especially the ones with long hair and loud drum sets and guitars about to be booted out of school or the house, or sent to Vietnam, fertile ground for experimentation was right in your own garage (once the Pontiac was moved out). Why not? It was My Generation.

A musical nexus for some was taking root in Central Park. “Everyone hung out at the fountain,” Peter Sabatino describes, meaning Bethesda Fountain. Only 16, and recently transfixed after hearing The Beatles play at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium (adjacent to his parents’ six-story apartment building), Peter and a few of his friends—two brothers, Larry and Leslie Weinstein, and Jerry Storch—did what tons of other teenagers were doing. They grew their hair and formed a band, and called themselves The Vagrants. Their drummer, Roger Mansour, was always looking for new material. “C’mon, listen to this guy Bert,” he urged, and soon the folky-pop troubadour with the frizzy hair was visiting the Sabatino home, guitar in tow, always with a fresh batch of songs.

Needing to find a new place to live and rehearse, Peter, Larry, and Jerry rented a house. Three were legally on the lease, but teenage logic dictated that for convenience sake, they should squeeze in two more—Leslie, in the apartment above the garage, and Bert, in the maid’s quarters above Leslie. When the owner stopped by unexpectedly, he was greeted at the door by the two illicit lodgers in a cloud of cannabis haze. All were evicted.

Fortuitously, The Vagrants got a seasonal gig on Long Island, where Bert hung out but was perhaps too tentative to muscle in on The Action House line-up. Psychedelia-stoked groups like Vanilla Fudge, The Illusion, and The Hassles (featuring a young Billy Joel on Hammond organ) shared the stage with The Young Rascals, Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels, and veterans like Wilson Pickett. The reputedly mob-owned club certainly lived up to its name—it was wild, inside and out—a teenage fantasyland where drugs, sex, and rock and roll ruled.

An online comment thread from 2009 reads: Met Bert Sommers [sic] out in Hampton Bays on Tiana Beach, next to a club called “The Eye.” Bert was a songwriter—had pages of them—but he was very shy. We had campfires on the beach. Week after week, everybody got to know each other, and Peter Sabatino and Larry from the Vagrants got Bert to do a song here and there onstage. He had a very pleasant way about him, got along with everybody.

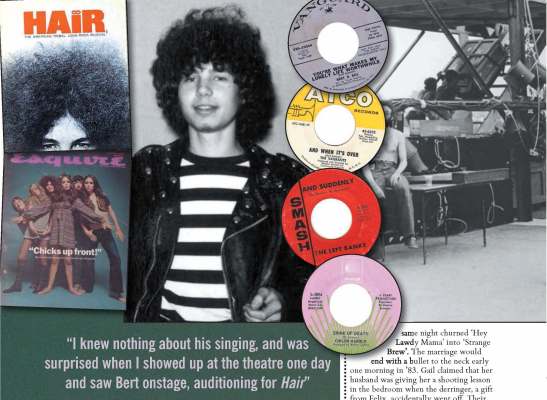

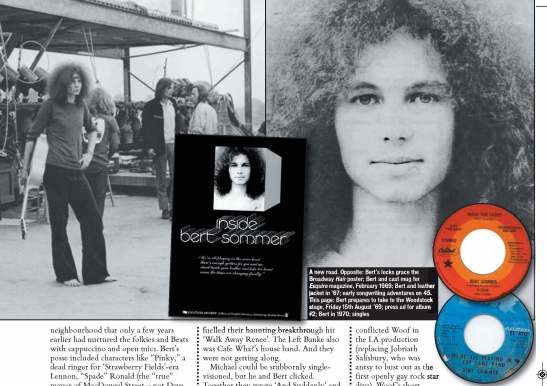

Writing for and with The Vagrants eventually led to ‘Beside the Sea.’ Bert’s song had started out as ‘Take You There,’ about a car, before the lyrics morphed into a vehicle for Mountain. This was the new incarnation of Leslie Weinstein—now Leslie West—and the song would be performed at the Woodstock festival Saturday night. Bert was on the tower, hanging out, absorbing the entire event with sweet relief that his set was behind him. Writing credits were shared with Mountain bass player Felix Pappalardi and his wife Gail Collins, whose credentials as a creative duo had been cemented in 1967 when Felix inadvertently stepped into Cream’s Atlantic recording studio, and later that same night churned ‘Hey Lawdy Mama’ into ‘Strange Brew.’ The marriage would end with a bullet to the neck early one morning in 1983. Gail claimed that her husband was giving her a shooting lesson in the bedroom when the derringer, a gift from Felix, accidentally went off. Their once “open marriage,” as well as the mystery surrounding the case, closed shut.

Another that Bert penned, solo, ‘And When It’s Over,’ had The Vagrants bend the tune to suit their soul-tinged garage-rock persona, while Bert’s ethereal rendition epitomized the post-coital musings of a peaceful, androgynous flower child. Albeit one who was about to be swallowed by cultural chasms, personal demons, and what would come to be known as the Woodstock Curse.

Record labels for 45s were offered like brass rings on the Central Park carousel. The Vagrants had grabbed Vanguard, and Bert followed with a single (‘You’re What Makes My Lonely Life Worth Living’) as part of the duo, Bert & Bill. Who Bill was, or is, remains a question even today.

*****

Everybody on West 3rd Street (Tony Pastor’s Downtown) knew Bert. Bert knew everybody. It was 1966 and the hipster became a hippie.——online comment

During the same Summer of Love, another group of boys barely out of high school gravitated toward the concrete chess tables in Washington Square Park after sundown. Just goofing around, they eventually made their way to clubs and cafes in the neighborhood that only a few years earlier had nurtured the folkies and Beats with cappuccino and open mics. Bert’s posse included characters like “Pinky,” a dead ringer for Strawberry Fields-era Lennon, “Spade” Ronald (the “true” mayor of MacDougal Street—not Dave Van Ronk—according to Chris Savage, who was right there with them), and “Russian George,” a Desolation Row-type lyric sprung to life. Sometimes a young woman joined them: Michele Hush, who would eventually become an editor at Rock Magazine.

“Hey, man.”

Then, “Hey, man,” back. Instant connection in front of Cafe Wha? on Minetta Lane. They all had the ubiquitous hair and knew each others’ faces, but didn’t utter more than a few grunts as conversation, guitars strapped to their backs. The one with the most distinctive presence (and, arguably, talent) grinned and cut in with a surefire topic of interest.

“Guess what—I’m in the new Left Banke.” Witness to Bert’s announcement was Alan Merrill, another New York City-born rocker, soon to vacate the Village and become the first Western pop star big in Japan. And later, lead The Arrows through London in the mid-70s with ‘I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll.’

“Do Tom, George, and Steve know about this?” was his retort, referring to the original band members, minus Michael Brown, whose father, Harry Lookofsky was a violinist and arranger (and guy with the studio). “Pater” had backed the Left Banke from the get-go, lending them the lush, baroque sound that fueled their haunting 1966 hit, ‘Walk Away Renee.’ The Left Banke also was Cafe Wha?’s house band. And they were not getting along.

Michael could be stubbornly single-visioned, but he and Bert clicked. Together they wrote ‘And Suddenly,’ and, along with ‘Ivy Ivy’ (penned by Tom Feher), this new Left Banke record began to climb the charts. Bert was now the lead singer. A pre-Spinal Tap Michael McKean was the other member to sidle into the splintered group, playing bass. The new group formation lasted about a New York minute. Just as the single was about to crack the Top 40, the disgruntled original band members’ lawyers put the kibosh on everything. The group never fully recovered, and Bert moved on to creative prospects that had been simmering on the back burner. But before he scraped the residue from the Left Banke off his shoes, he wrote ‘Brink of Death,’ recorded by Childe Harold. Bert was just nineteen.

Yin and yang thespians James Rado and Gerome Ragni had been working on a musical about the new American counterculture as far back as 1964. Rado began to notice a kid on his regular bus route. He looked perfect for a member of The Tribe. “He had a wonderful head of hair, but what really drew me in was his friendly smile. Actually, it was more of a mischievous grin. I told him about the musical and that he should audition. I knew nothing about his singing, and was surprised when I showed up at the theater one day and saw Bert onstage, auditioning for Hair.”

He came in as just an ensemble player, and evolved to being cast as the sexually conflicted Woof in the L.A. production (replacing Jobriath Salisbury, who was antsy to bust out as the first openly gay rock star diva). Woof’s short, memorable solo ‘Sodomy’ encouraged the audience to Join the holy orgy Kama Sutra, everyone! while Bert’s own head of hair spiraled over the west coast Playbill. Soon he was reprising the role back on home turf: Broadway.

New York cast member Robert I. (Rubinsky) remembers Bert as having a sweet energy. In the midst of the tribe, he also felt a particular rapport with Bert. “We weren’t real hippies; we were borough guys. I grew up in Brooklyn, he grew up in Queens. He had a beautiful voice; his whole vibe and look was angelic. He had ‘something.’ He didn’t blend or disappear. If Bert had been born just ten years earlier, he would have fit right in with the Brill Building writers, knocking out songs with Carole King, Neil Sedaka, Ellie Greenwich.”

At 25, Artie Kornfeld was the youngest V.P. at Capitol Records when agent Dominic Sicilia dropped off a client cassette at Artie’s Sutton Place apartment. “I recognized talent,” Artie credits both himself and Bert—and signed him on. Now Bert had a major record contract and a boy wonder producer. It wasn’t just business, however. A metaphysical bonding had begun before the ink was dry.

Kornfeld was a borough guy, too. He had a lot of pop hits in his arsenal, both as a co-writer and producer, and he gave Bert full rein to explore on his debut album, The Road to Travel. The cornucopia of musical outpouring is impressive, but made Bert hard to market. Vocal delivery and production ranged from to Bacharach-esque to hard-driving folk to ‘Itchycoo Park’–type ear worm. Bert shifted musical gears often, like a sports car driver knowing he could take the sharp curves—ones that offered the best views of both the rainbow and the abyss. His lilting delivery still has the power to disarm the listener as darkly honest lyrics reflect Bert’s firsthand experience with emotional and familial damage, as well as a growing familiarity with drugs.

As with anyone still in his teens, Bert’s lyrics also concerned a hopeful and persistent search for love. ‘Jennifer’ was a popular name, but this was no marketing ploy. Bert wrote the tremulous, then emotionally volcanic song for his Hair co-star, Jennifer Warnes. Internet speculation ensued after a clip surfaced on YouTube, decades later: Was this a fantasy love affair or something more? In an email, his muse looks back on that time: “Bert did tell me that he wrote a song for me, and he played it for me once, but I never took that gesture as any indication of intended romance. He apologized for embellishing it a bit with the ‘kissing her here in the grass’ part. I remember little, except his general sweetness and kindness throughout that year we worked together. I never saw Bert after Hair.”

Discovered in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1994 TV documentary Woodstock Diary, this song (and Bert’s performance) was revelatory. ‘Jennifer’ was the golden key that began to unlock the years of the Woodstock Curse.

Artie Kornfeld, Bert’s friend and mentor, and Woodstock co-creator, had sold film rights to Warner Brothers a couple of days before the event, averting a total financial disaster. Michael Wadleigh’s subsequent ground- and record-breaking 1970 documentary, Woodstock, became the de facto reference source, despite a few glaring omissions. One flickering candle of an omission was Bert Sommer. Over the years, claims of too-dark footage kept Bert in the Warner Brothers vaults—not the fact that he happened to be on a competing record label.

Next he was cropped out of a photo for Life magazine’s special Woodstock issue, and over the coming decades, Bert was ignored and/or forgotten on anniversaries—not even included on a memorial plaque added to the original site at Bethel Woods, in 1984.

Bert had fallen through the cracks and was kicked to the curb. All of this hurt him. Deeply.

*****

A 1985 Albany cable TV interview on Sarge Blotto’s Hot Seat begins by inadvertently chopping off Bert’s latest song, ‘Don’t Take Candy from Strangers’ (co-written with Eddie Angel, now of Los Straitjackets). Then the introduction—riffing off of both Woodstock and Saturday Night Live comedian Billy Crystal— “ . . . my inimitable and always marvelous guest . . . Bert . . . uhh . . .Bert Sommer.” There is a joking familiarity between the two, and a blurring of boundaries of who is in charge. The host (Greg Haymes/Sarge Blotto) smokes a cigarette in a black leather jacket, and seems unable to be quite as cool as he’d like—possibly because this is his premier broadcast, but most likely because Bert is known to be a loose cannon, and a pro at stealing any available spotlight (no matter how remote), with his charm and reckless charisma.

A bottle of beer in hand, Bert swivels in his chair, leans back, then forward into the camera, sideways into Sarge—and down toward the floor, looking for his early albums and posters and props. Relaxed yet fidgety, goofy yet sincere, Bert maintains his strobing megawatt grin. Not until he picks up a guitar and breaks into his closest-to-being-a hit, ‘We’re All Playing in the Same Band,’ is he his truest self.

Written in the afterglow of Woodstock, charting on Billboard at #48, Bert’s song still ignites something that the low-budget video poignantly captures. The lyrics and bouncy melody mirror both Bert’s own timeless innocence and that of the era that allowed him to come of age as a fully formed artist. The years have been kind to it.

Easing into his God-given gift, that voice!—which will never abandon him, not even at the very end of his life, just five short years away—Bert is at peace with himself. The Woodstock Curse nowhere in sight.

***

With many thanks to Jesse Sommer

copyright Sharon Watts 2019

Shindig! – Issue #94

Share this:

Related

5 comments on “Bert Sommer — Shindig! Issue #94”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on September 2, 2019 by DIRNDL SKIRT in Bert Sommer, Published Article and tagged Action House, Alan Merrill, And When It's Over, Artie Kornfeld, Bert Sommer, Cafe Wha?, Chris Savage, Hair, Ira Stone, James Rado, Jennifer, Jennifer Warnes, Left Banke, Leslie West, Lost Bard of Woodstock, Michael Brown, Paul Simon's America, Peter Sabatino, Roger Mansour, Sarge Blotto's Hot Seat, Shindig Magazine, Summer of Love, The Action House, The Vagrants, Tom Feher, We're All Playing in the Same Band, Woodstock Diary, Woof.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2H7Gt-kRRecent Posts

Categories

Archives

- February 2024

- October 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- August 2021

- September 2020

- August 2020

- June 2020

- January 2020

- September 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2016

- March 2016

- September 2015

- July 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- July 2014

- March 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- August 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

Brilliant read.

Thank you, Scott! It was fascinating to research. Just a little before my time in the Village.

Pingback: Woodstock, New York, illustrations – an interview with artist Sharon Watts – blue tram

Pingback: Woodstock, New York, illustrations - an interview with artist Sharon Watts - bluetram

Pingback: Bert Sommer in Brockport (“it was the ’70s”) . . . and a bit of my M.O.) | Sharon Watts Writes